(Republished from Huffington Post)

By Giacomo Tognini and Khairuldeen Makhzoomi

Five years since Muammar Gaddafi’s 42-year rule came to an end in the heady days of the Arab Spring, what once seemed like the beginning of a bright future for Africa’s richest country instead collapsed into chaos. Its leaders are struggling to establish a unity government that can reconcile the country’s warring factions and battle the common enemy of the Islamic State. Even with the unity provided by the threat of IS, there are stark challenges ahead to ensure a secure and democratic Libya.

Months of negotiations between the country’s rival parliaments in the capital of Tripoli and the eastern city of Tobruk produced a unity government last December. Led by Prime Minister Fayez al-Serraj, the internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) established itself in the capital in May. Despite gaining the approval of the previous parliament in Tripoli and the kaleidoscope of local militias loyal to it, the GNA has yet to receive a mandate from Tobruk and its forces, the so-called Libyan National Army (LNA) under the control of the mercurial General Khalifa Haftar.

Libya has been dominated by small militias and city-states since a national government broke down in 2014, but they are slowly setting aside their differences to fight the expanding reach of the Islamic State. IS has established a “maritime Mosul” in the coastal city of Sirte — Gaddafi’s hometown — and enjoys the allegiance of former Al-Qaeda jihadists in Tunisia. Many regional and foreign officials, including the Obama administration and its European allies, have acknowledged the need to develop specific strategies to combat IS’ influence in Libya.

The fight will be challenging. As the political deadlock persists, IS continues to carry out terrorist activities and has launched several attacks on Libyan Christians. In February 2015 IS executed 21 Christian Egyptians on a Libyan beach, and in its most recent attack last March it struck across the border in Tunisia, killing more than 54 civilians and members of Tunisian security forces, including a young girl.

The United States, which played a central role in the NATO aerial campaign that helped oust Gaddafi in 2011, has returned to the fray. In February, a U.S. air strikeon the seaside town of Sabratha targeted an IS leader linked to attacks in Tunisia last year. The same month, American Defense Secretary Ashton B. Carter presented a military plan that calls for as many as 30 to 40 airstrikes in four major areas in Libya. The plan hopes to cripple the group’s major bases outside Iraq and Syria, and President Obama acknowledged days later that the U.S. “will continue to use the full range of tools to eliminate ISIL threats” wherever they may be.

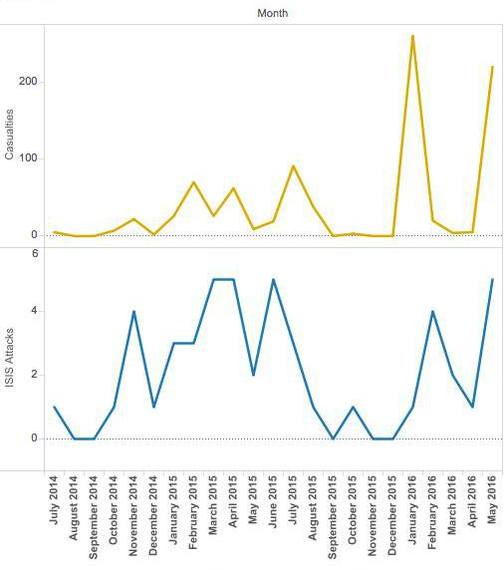

ISIS Attacks in Libya July 2014 to mid-May 2016, casualties include deaths and injuries. Sources: Reuters, CNN, Libya Herald

ISIS Attacks in Libya July 2014 to mid-May 2016, casualties include deaths and injuries. Sources: Reuters, CNN, Libya Herald

European countries have also joined the fight, with the United Kingdom deployingits Special Air Services on undercover missions to help combat IS forces. Last month, a memo leaked to the Guardian confirmed that SAS members had been aided by Jordanian intelligence, adding that Jordan’s King Abdullah had addressed members of the U.S. Congress about his country’s involvement in the Libyan crisis. Last week over 20 countries, including regional powers and Libya’s neighbors, met in Vienna for a conference on countering IS in Libya. They pledged to recognize the GNA as the legitimate government and explored the possibility of removing the 5-year-old arms embargo on the country. In a dramatic departure from earlier policy, even Russia and China backed the plan.

Foreign military personnel — including French, British, Italian, and American forces — have been spotted by Libyan media carrying out reconnaissance missions and collaborating with local militias. The U.S. is already engaged in a campaign of drone strikes against IS in the country, and shifted more surveillance drones there for intelligence gathering. American and French special forces have deployed to the airport in the eastern city of Benghazi, which may reopen soon to bring in Western arms and supplies to aid the war effort.

Benghazi is under the control of Haftar’s LNA, which, unlike its western rivals, possesses an air force. A high-ranking Gaddafi ally until the 1980s, when he fled tocollaborate with the CIA, Haftar returned during the revolution and recently scored a string of important successes in the east. After pacifying Benghazi in April and expelling the presence of Ansar al-Sharia, Libya’s al-Qaeda affiliate, the LNA moved west to target IS and Islamist forces in Derna and Ajdabiya.

His heavy-handed approach is not popular everywhere in the country. The LNA still refuses to recognize the GNA’s authority, and Prime Minister Serraj wants Haftar to halt military operations until all anti-ISIS forces can unite under the leadership of new GNA defense minister Mahdi al-Barghathi. This ignores the wishes of Libya’s foreign partners, who repeatedly stress the need to give Haftar an important role in military operations. In the west, the LNA has skirmished with militias from Misrata, a powerful city-state that supports the GNA. Further sowing distrust is Haftar’s recent decision to allow Gaddafi loyalists to return to the country and contribute to the anti-ISIS effort, including an alliance with pro-Gaddafi tribes in the east. Even the dictator’s widow, exiled in Oman, was allowed home.

There is still hope for reconciliation, as the LNA-aligned Tobruk parliament is planning to hold a new vote soon to endorse the GNA. The parliament’s speaker, Aguila Saleh Issa, faces foreign sanctions and could join the GNA in exchange for more positions for easterners. In the south, a peace agreement brokered in November halted fighting between Tuareg and Toubou tribes, who declared support for the GNA. After a series of battlefield setbacks, Misratan forces took the town of Abu Grein from ISIS last month, launching a campaign to reach Sirte. They entered the city last week after a lightning offensive, and a battle is now raging at the heart of ISIS’ Libyan stronghold

The anti-ISIS effort could be the catalyst to unite and rebuild Libya, but much work remains. Marginalized groups like the Amazigh still reject the GNA and desire further autonomy, and foreign powers are still disunited in their support, with Egypt and the United Arab Emirates staunchly supporting Haftar’s LNA.

Map of territorial control in Libya as of May 2016. Source: The Economist

Map of territorial control in Libya as of May 2016. Source: The Economist

The problems do not end there. According to former UN Special Coordinator Peter Bartu, Libya is unlike any other post-conflict country in the world. “I was so struck by how strange and different Libya seemed that I felt that it required special measures,” he says. “Libyans have really struggled with [the idea of] representation, and I think part of the struggle is because of that unique experience under Gaddafi.”

Gaddafi’s 42 years of quixotic rule virtually abolished all the country’s institutions, replaced with a veneration of the “Brotherly Leader” and his peculiar ideology. “You had no institutions and it was really the most radical democratic experiment anywhere, so they don’t understand parliaments or elected representatives,” says Bartu. “[Libyans] find it hard to relate to decision-making mechanisms that aggregate preferences and sometimes might go against what you think is right.”

Unlike neighboring Tunisia, where Islamist parties approved a liberal constitution, Bartu believes Libya’s Islamists present a different challenge. “When I was dealing with Ansar al-Sharia in 2011 they were very fixed in their ideas,” he says of his experience mediating for the UN in Benghazi. “They are Salafist [and] have a very limited view of government, they’ll accept an election for ruler or leader but [not] for parliament because legislation comes from the Quran, not from any other source.”

Libyans still have to come to terms with how to reconcile with Gaddafi-era officials and provide a role for them in rebuilding the country. “Everyone had worked for Gaddafi, like the Ba’athists in Iraq — what role do you have in future Libya for people who had blood on their hands, were corrupt or just bureaucrats who had been part of the original system?” asks Bartu. “There’s now more than a million and a half [Libyans] who are still outside the country, who are needed in the reconstruction [but] don’t feel they have a place to come back.”

Despite the seeming abundance of chaos, there are islands of stability that afford a measure of hope. “There are a whole range of quite positive local government arrangements emerging right across the country, like local village councils, local municipalities,” says Bartu. “[They’ve been] able to stay away from the fighting and run their communities quite successfully, which is really terrific for Libya moving forward.”

Long accustomed to rugged individualism in the face of a brutal regime, Libyans must come together to construct a democratic state from scratch and defeat the scourge of ISIS. The group rapidly gains strength from former al-Qaeda members in the area by the day, and unless a unified intervention begins soon, it might become too late for foreign powers to intervene.

If Libyans can set aside their differences to eliminate the terror of the Islamic State and liberate Sirte, they will be one step closer to fulfilling the promise of the 2011 revolution. Then comes the hard part: building a democratic state that serves all Libyans, not just those of your hometown, religion, or ethnic group. Unlike Gaddafi’s fictitious version of direct democracy, the most radical democratic experiment in history could yet prove to be in Libya.

Khairuldeen Al Makhzoomi is a researcher at the Near Eastern Department of UC Berkeley. He holds a degree in Political Science and Near Eastern Languages and Literature from UC Berkeley. Currently working on a research “ Obstacles to National Reconciliation in Iraq “, the founder of “United 4 Iraq” Facebook page. Khairuldeen also writes for Berkeley Political Review.

Email Address: [email protected]

Giacomo Tognini is a freelance writer, student and researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, where he is also the Senior World Editor of the Berkeley Political Review. He has worked as a reporter for The Jakarta Globe, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, and The Daily Californian. He currently translates from Italian, French, and Spanish for the online news startup Worldcrunch.

Email: [email protected]